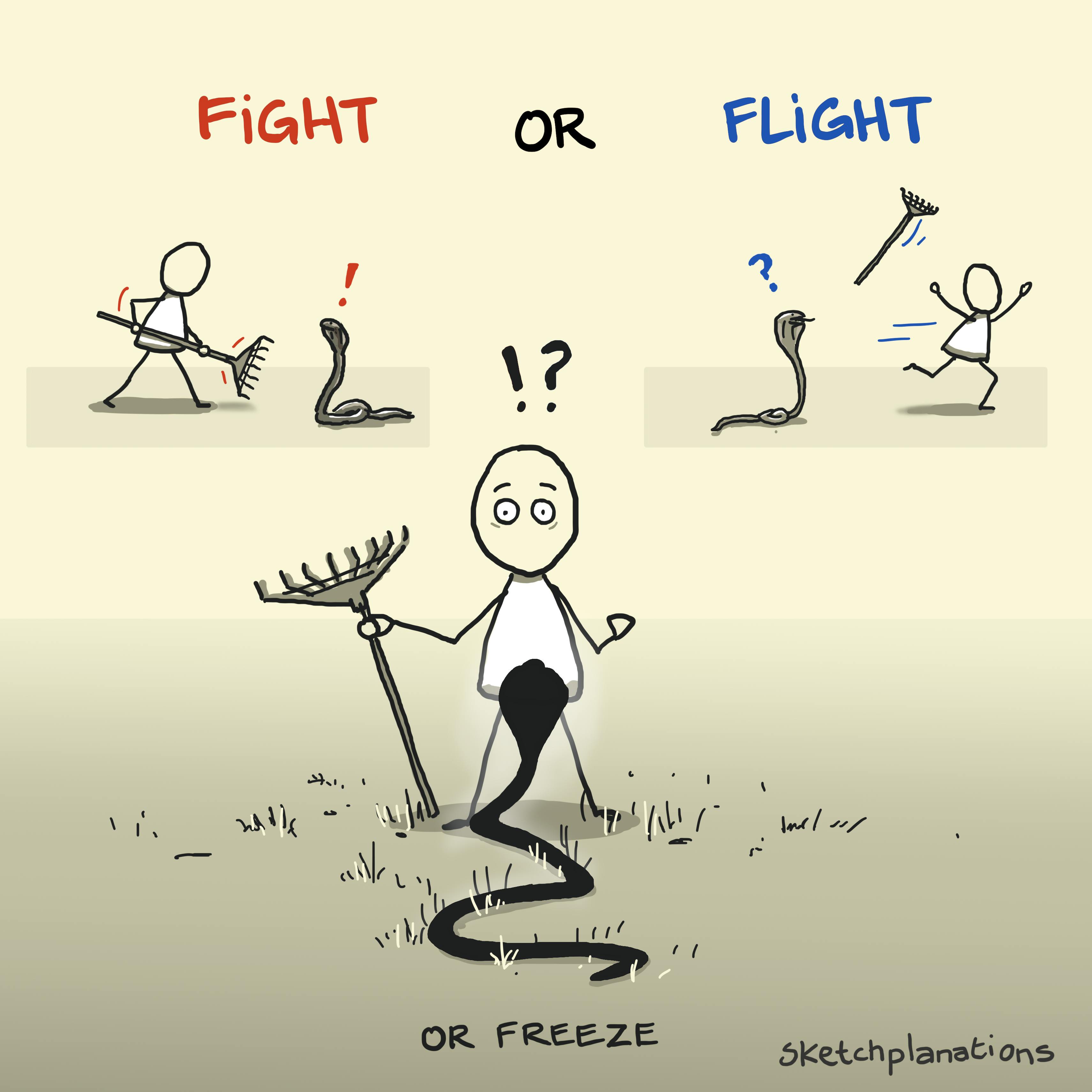

Fight or Flight

👇 Get new sketches each week

The fight-or-flight response is our body's automatic and ancient response to perceived threats or danger. This innate physiological response in animals and humans prepares us to either confront a threat (fight) or flee from it (flight). This mechanism, often referred to as entering fight-or-flight mode, likely played a critical role in our survival.

Face to face with a tiger

At the annual Wildlife Photographer of the Year Awards, I saw an astonishing photo of a tiger surprising workers in a field (Tiger Run by Nejib Ahmed ). Everyone is in flight mode except one man, much braver than me, who perhaps through instinct has stood to fight, staring down the approaching tiger with a long stick. The photo is captivating in its drama and struck me as a perfect fight-or-flight example in action. Thankfully, no one—including the tiger—was hurt in this instance.

The adrenalin that can flood our bodies during such moments may sometimes give us strength to do what we didn't expect, surprising ourselves with what we are capable of—Nicola Morgan, when discussing the amazing teenage brain , gives an example of her leaping a 5ft fence and looking back with amazement. Sudden strength or speed like this is a well-known fight-or-flight symptom.

Reptilian brain, Lizard brain

The fight-or-flight response is linked to theories about how different parts of the brain developed during our evolution. Modern research has corrected some aspects of this idea, but the basic concept remains.

The most primitive parts of the brain—those we may share with, say, dinosaurs—are responsible for automatic behaviours like protecting territory, aggression, fear and fending off danger. This is often referred to as the reptilian brain or lizard brain. These brain areas are key to our survival instincts and play a critical role in activating fight-or-flight mode.

Years of evolution since then have given us brain structures like the limbic system, which is responsible for our emotions and social behaviours. The amygdala, part of the limbic system, is especially important in triggering fear and the fight-or-flight response.

Later, the neocortex evolved, enabling humans to assess threats rationally, solve problems, and make decisions—giving us more control over how we respond to fear or anxiety.

The response, also illustrated by the snake rearing up in the sketch, is a fallback to our oldest instincts from the oldest parts of our brain when faced with a threat, so the theory goes.

Freeze, Flight, Fight, Fright

Fight-or-flight psychology, coined by physiologist Walter Cannon in 1915, is only part of a broader spectrum of acute stress responses. A more accurate sequence we experience may be freeze, flight, fight, or fright .

Freeze: Our immediate reaction to danger might be to "stop, look, listen," remaining hyper-vigilant while we assess the threat, and perhaps hope by not moving, the dinosaur won't spot us.

Flight: We may flee the situation to safety.

Fight: If escape isn't possible, we might fight back, as shown by the brave individual in the tiger photo.

Fright: This might include panic and immobility, playing dead in case a predator decides we're not worth eating after all.

As you see, the updated list continues with excellent alliteration, which no doubt helped make the idea sticky in the first place (other proposals add fawn, faint, flock and more).

When Fight-or-Flight Doesn't Help

While the tiger scenario shows our ancient brain instincts at work, most modern-day situations don't involve life-or-death threats. However, we may still enter fight-or-flight mode during stressful, anxiety-inducing moments, such as public speaking, a challenging work interaction, or a difficult conversation.

In these cases, our age-old reactions may not serve us well. The same ancient brain that would help us survive a predator may now cause us to avoid daunting tasks. Whether it's a work presentation, a cold sales call, or confronting a personal issue, we may feel the urge to retreat from the action and get a snack from the kitchen instead.

When our ancient instincts—so finely tuned for survival—are no longer serving us in modern situations, it's helpful to pause and let our higher-order thinking take the lead. Techniques like box breathing or meditation help calm the body and mind, allowing us to move beyond fear and resistance. By doing so, we can overcome the automatic urge to "fight or flight," or even freeze or fright, and instead respond with clarity, control, and confidence.

Also see:

- Box breathing

- The spotlight effect

- Don't make important decisions on an empty stomach

- Cognitive overhead

- See Big Ideas Little Pictures for Melissa Dahl's Awkwardness Vortex and the technique of reframing anxiety as excitement