Congested Equilibrium

👇 Get new sketches each week

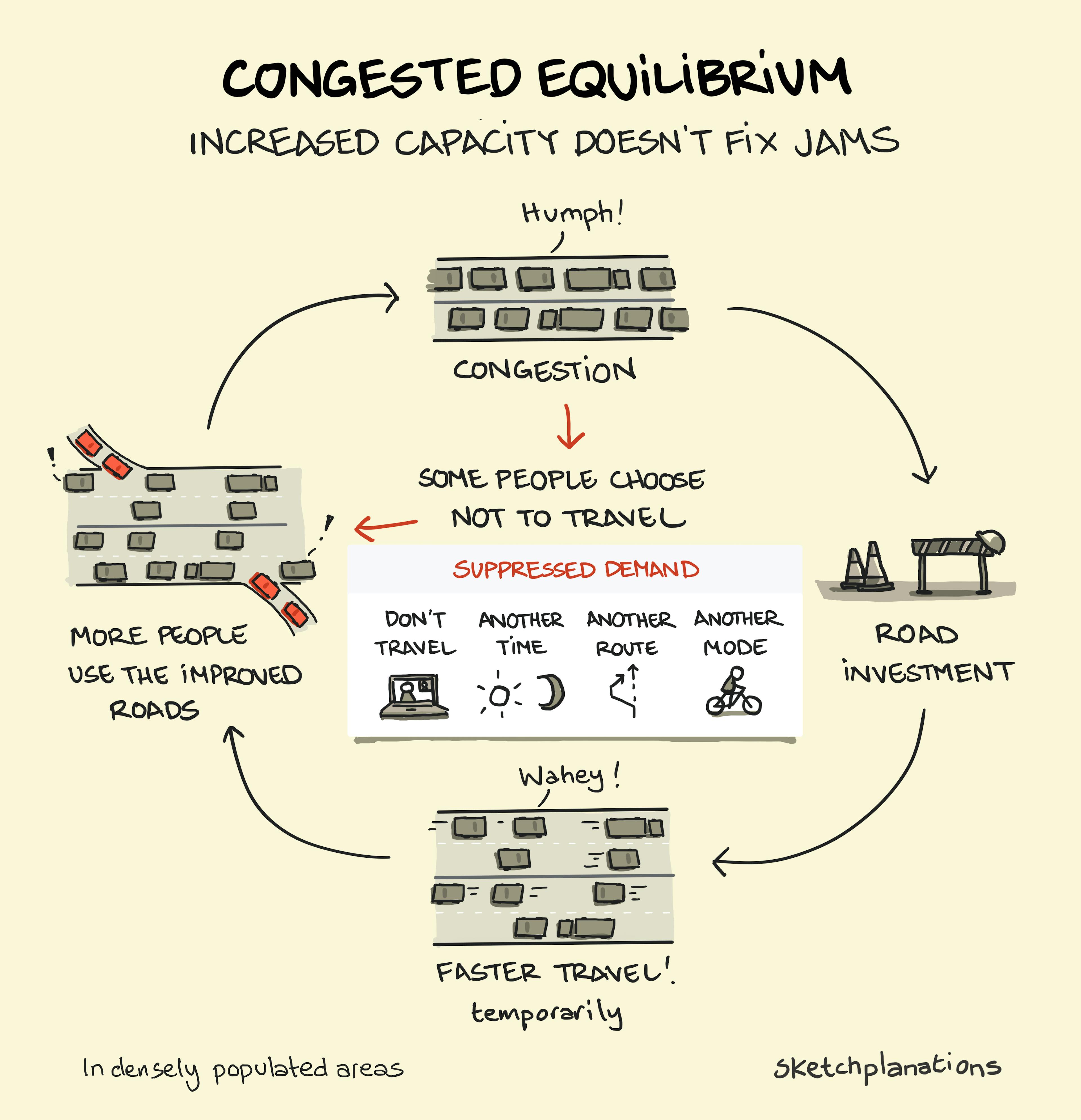

You, like me, probably dislike being stuck in traffic. If you live in a densely populated area, it's likely that for at least some of the day, a number of the major roads around you are congested, i.e. there's a lot of traffic, and it tends to go slowly. Unfortunately, as I learned with the phrase "Congested equilibrium," from UCL Professor David Metz, there's no magic wand to wave for roads that will run smoothly and get you to your destination with minimal hassle.

What is Congested Equilibrium?

It's easy to assume that there's a fixed amount of traffic on the roads. So if your local road agency widens, improves, or adds alternative fast roads to get to your destination, you might think that traffic will improve. And it does, but only briefly. Then somehow the traffic jams return.

The reality is that in densely populated areas, traffic congestion tends to be self-regulating. When driving is slow and somewhat painful, people who would have driven make other choices:

- choose not to travel—maybe a video call instead, or just don't go to the shops

- take a different means of transport such as a train or bike

- travel earlier or later

- take different routes

After millions in road investment—perhaps widening roads or building a bypass or extended stretch of motorway—traffic runs faster, for a time.

But when people realise that roads are again a good option for travel, some of those who had chosen not to drive or didn't use that route before, jump back in the car and make use of the new, improved roads. And the increased traffic once again leads to congestion that gets progressively worse until people decide to make other choices once again.

Traffic congestion is a feature of road networks that is very hard to avoid because densely populated areas have a vast reserve of these suppressed trips—people who would drive if the traffic was better—ready to make use of an improved road network when it arrives.

From congested equilibrium comes the maxim in travel planning circles: "You can't build your way out of congestion."

I learned about congested equilibrium and the general trials and challenges of travel planners in the book Good to go? Decarbonising Travel After the Pandemic by Professor David Metz. Although the book had less to do with decarbonising than I expected, it did teach me a great deal about the challenges and considerations of travel planning.

Related Ideas to Congested Equilibrium

- Marchetti's Constant—as we travelled faster, we travelled farther, maintaining about an hour's daily travel time

- Laws of Expansion

- Isochrones

- Pollution is highly localized: take the back streets

- Travel choices in London

- Our Senses are Built to Take in Information at Human Pace

- Jevons paradox

- Cobra effect

- Frequency is freedom, a line from Jarrett Walker about the impact of frequency on public transport. I haven't sketched this yet, but it's so catchy I thought I'd share

More I learned About Traffic

For the last half a century or so, the average daily travel time has remained unchanged. This is despite huge investments in road networks in urban areas.

When I find myself stuck in and complaining about traffic, my mind flashes back to a memory of a billboard in San Francisco that read, "You are not stuck in traffic. You are traffic." Then I feel better about my fellow drivers.

What people like least is uncertainty about journey time. So digital navigation, as exemplified by Google Maps, is doing an amazing job at giving us peace of mind here. Until ChatGPT, I put Google Maps as the best app out there.

In European cities you tend to find either high public transport use (like London), or a lot of cycling (think Copenhagen). But you don't tend to find high levels of both. Copenhagen's proportion of car journeys is similar to London's. The car has an appeal when the roads allow it. Improving cycling tends to pull people from public transport and vice versa rather than pull people from their cars.

Of David Metz' points that stick with me is also that the most effective way to reduce car usage in city centres, in conjunction with improving other means of travel, is to reduce the availability of parking.

Also, each city is different: some cities like London are spread wide and the distances are large, some have more cooperative weather, some have a lot of hills, and some are in countries where cars are a significant status symbol. There's no one-size-fits-all.