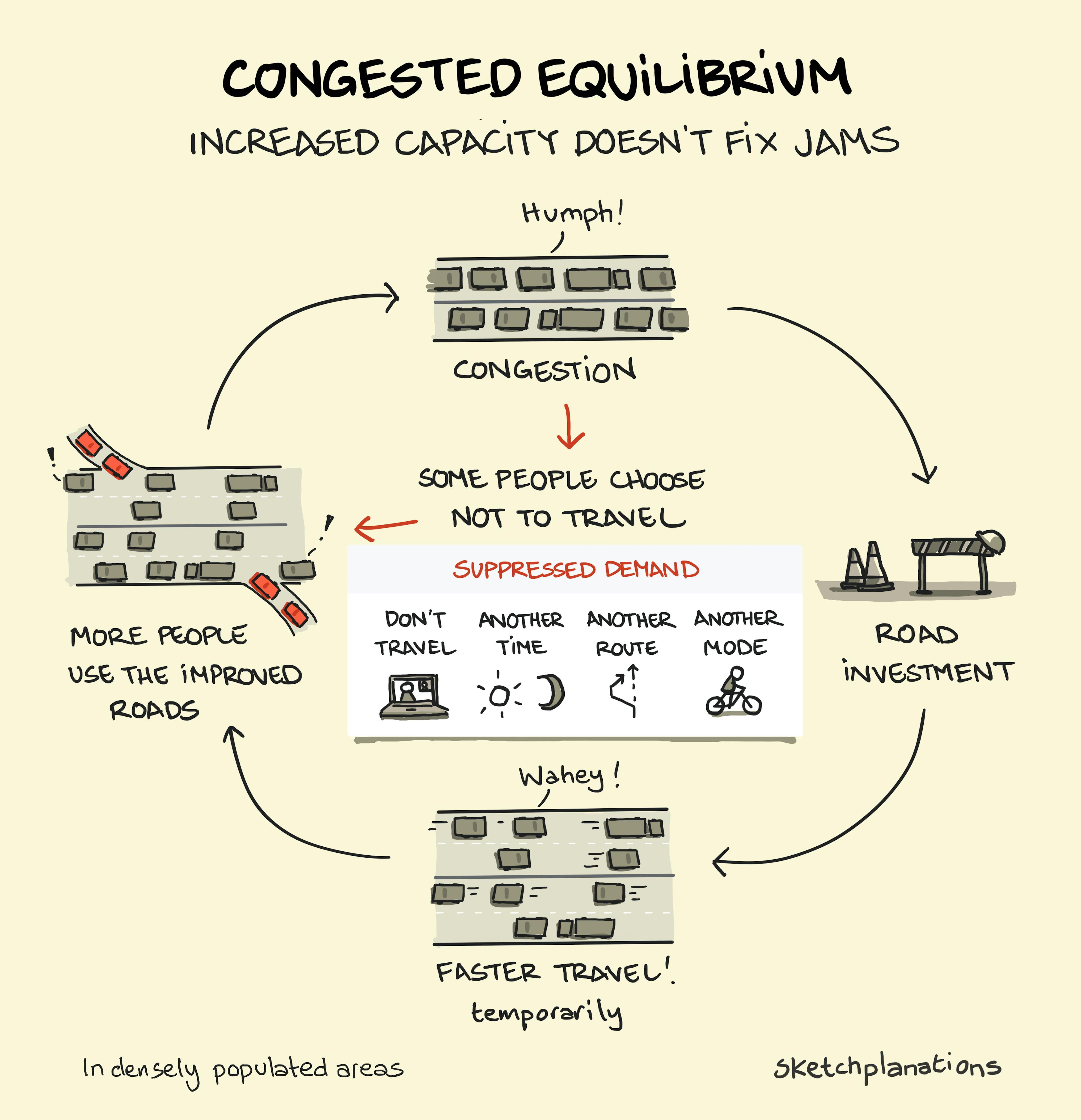

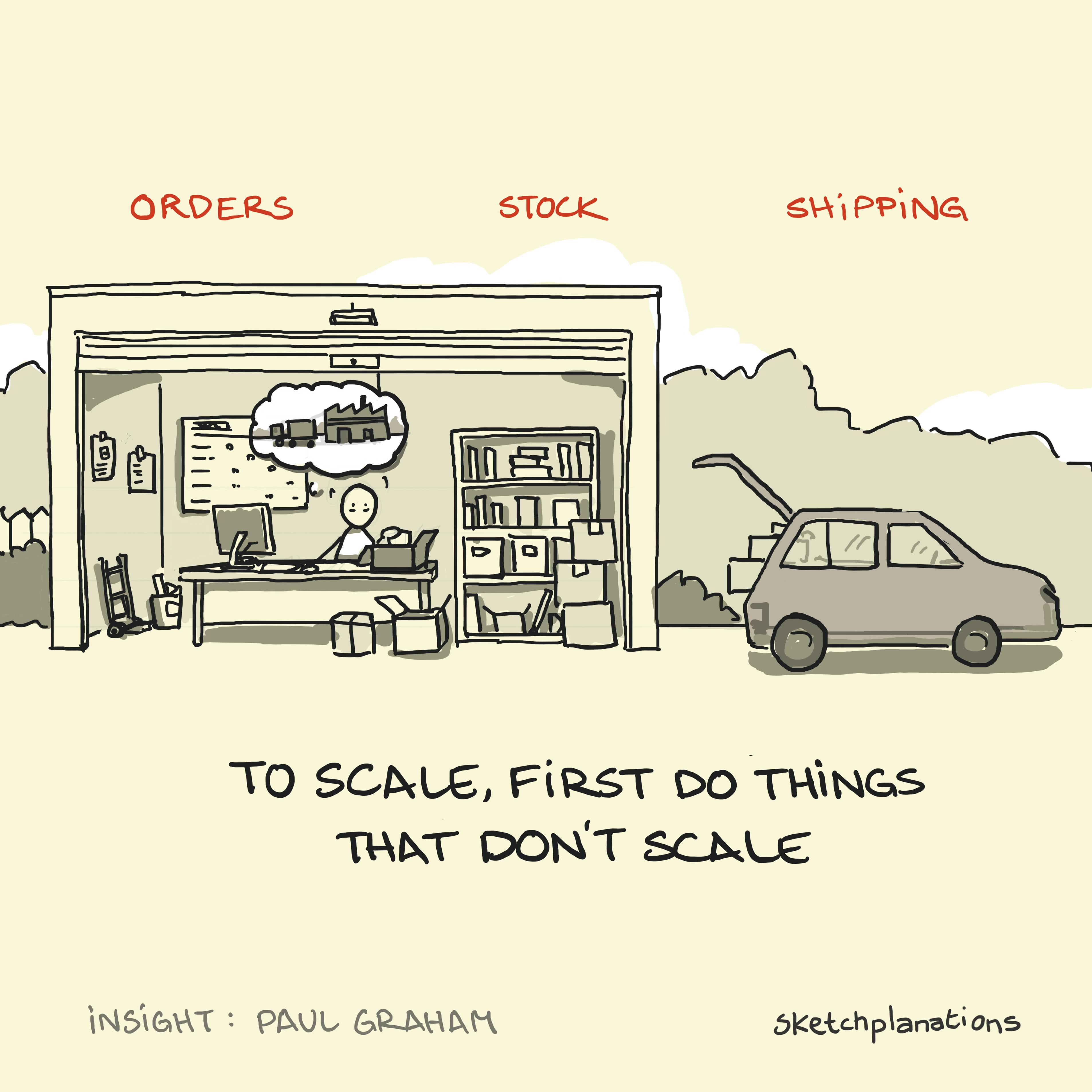

The startup paradox: grow big by starting small One of the seeming contradictions in a company's journey is that, as Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator, points out in a well-known essay, to get your company operating at scale, you first have to do things that don't scale. Why does this sometimes seem like a contradiction? If we picture large, successful tech companies, it's easy to imagine all sorts of clever technology and automation that makes everything work automatically. How else would you serve thousands, if not millions, of users simultaneously? In the early days, it's easy to think of a new offering or feature, or even the very core of the business, as "that's too manual, we can't do that," and then keep building and guessing. But the reality is that doing things that don't scale at first is the way many companies get to massive scale. Brian Chesky, founder of Airbnb, shared a classic do things that don't scale example. In the early days, he and his cofounder went door-to-door to the first users of the platform, photographing apartments and asking customers what they could do better. They processed and uploaded photos manually, managing with spreadsheets and some hired help until they later automated the process. Why Do Things That Don't Scale Here are some of the advantages I've seen of starting with things that don't scale: You learn what customers need. The more time you spend close to your customers, ensuring your product works for them, the more empathy you develop for what it's like to be in their shoes. This empathy will help you over and over again. You can start now. Before investing a lot of time building software or figuring out how to automate, you can begin learning immediately. It's cheaper. You don't have to design, spec and build for weeks before launching. Everything you later build will be useful. When running it manually gets too painful, you know that whatever you build to automate the process will help you immediately. You find product-market fit faster. Running things manually helps you experiment and adapt quickly. It's easier to kill things that don't work. It's less painful to stop doing a manual process than to rip out features or code customers aren't using. Examples of Doing Things That Don't Scale It doesn't have to be your whole business—it could be a new feature or tool. If your platform would eventually generate a dashboard automatically, maybe the first ones you just create by hand. If you need to manage people's availability, you can start with a calendar on a whiteboard. Marketplaces that operate at thousands of transactions a day started with a spreadsheet and a phone. Jeff Bezos packed and delivered the first books shipped by Amazon. Hewlett-Packard famously started in a garage. If your business is already at scale and you want to try something new, see if you can run it manually for a small group of users first. If you can make it work for them—fine-tuning out all the issues—then there's a good chance you can scale it more widely. I've personally made the mistake of aiming for scale too early. At my first startup, we spent longer than we should have building what we thought was needed for a system that worked automatically, rather than just getting started—even if it meant taking more manual steps. I've also been part of successful new products and services that we initially ran manually, using spreadsheets and people's effort, before fully automating them, sometimes many months later. As Brian Chesky says: Do it until it hurts, then automate it away. Learn more: Paul Graham's original essay: Do Things that Don't Scale I always recommend the very first Masters of Scale podcast episode with AirBnB's Brian Chesky on this topic. Not directly related, but this short article on the AI agency, and how starting by operating manually, and then using technology to automate and improve efficiency also affected my thinking on this: The AI Agency, Tomasz Tunguz Seth Godin wrote:

"The thing is, you don’t get to 3% of the market by trying for 40% and failing. You get there by embracing the 1% and doing such a good job that the word spreads." - Big scale, Big impact, Seth Godin Related Ideas to Do Things That Don't Scale The Business Flywheel Fauxtomation Painkillers and vitamins The Long Nose of Innovation Sexy Value Desire Paths Overnight Success The Knowledge FunnelThe startup paradox: grow big by starting small One of the seeming contradictions in a company's journey is that, as Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator, points out in a well-known essay, to get your company operating at scale, you first have to do things that don't scale. Why does this sometimes seem like a contradiction? If we picture large, successful tech companies, it's easy to imagine all sorts of clever technology and automation that makes everything work automatically. How else would you serve thousands, if not millions, of users simultaneously? In the early days, it's easy to think of a new offering or feature, or even the very core of the business, as "that's too manual, we can't do that," and then keep building and guessing. But the reality is that doing things that don't scale at first is the way many companies get to massive scale. Brian Chesky, founder of Airbnb, shared a classic do things that don't scale example. In the early days, he and his cofounder went door-to-door to the first users of the platform, photographing apartments and asking customers what they could do better. They processed and uploaded photos manually, managing with spreadsheets and some hired help until they later automated the process. Why Do Things That Don't Scale Here are some of the advantages I've seen of starting with things that don't scale: You learn what customers need. The more time you spend close to your customers, ensuring your product works for them, the more empathy you develop for what it's like to be in their shoes. This empathy will help you over and over again. You can start now. Before investing a lot of time building software or figuring out how to automate, you can begin learning immediately. It's cheaper. You don't have to design, spec and build for weeks before launching. Everything you later build will be useful. When running it manually gets too painful, you know that whatever you build to automate the process will help you immediately. You find product-market fit faster. Running things manually helps you experiment and adapt quickly. It's easier to kill things that don't work. It's less painful to stop doing a manual process than to rip out features or code customers aren't using. Examples of Doing Things That Don't Scale It doesn't have to be your whole business—it could be a new feature or tool. If your platform would eventually generate a dashboard automatically, maybe the first ones you just create by hand. If you need to manage people's availability, you can start with a calendar on a whiteboard. Marketplaces that operate at thousands of transactions a day started with a spreadsheet and a phone. Jeff Bezos packed and delivered the first books shipped by Amazon. Hewlett-Packard famously started in a garage. If your business is already at scale and you want to try something new, see if you can run it manually for a small group of users first. If you can make it work for them—fine-tuning out all the issues—then there's a good chance you can scale it more widely. I've personally made the mistake of aiming for scale too early. At my first startup, we spent longer than we should have building what we thought was needed for a system that worked automatically, rather than just getting started—even if it meant taking more manual steps. I've also been part of successful new products and services that we initially ran manually, using spreadsheets and people's effort, before fully automating them, sometimes many months later. As Brian Chesky says: Do it until it hurts, then automate it away. Learn more: Paul Graham's original essay: Do Things that Don't Scale I always recommend the very first Masters of Scale podcast episode with AirBnB's Brian Chesky on this topic. Not directly related, but this short article on the AI agency, and how starting by operating manually, and then using technology to automate and improve efficiency also affected my thinking on this: The AI Agency, Tomasz Tunguz Seth Godin wrote:

"The thing is, you don’t get to 3% of the market by trying for 40% and failing. You get there by embracing the 1% and doing such a good job that the word spreads." - Big scale, Big impact, Seth Godin Related Ideas to Do Things That Don't Scale The Business Flywheel Fauxtomation Painkillers and vitamins The Long Nose of Innovation Sexy Value Desire Paths Overnight Success The Knowledge FunnelWWW

Read more…