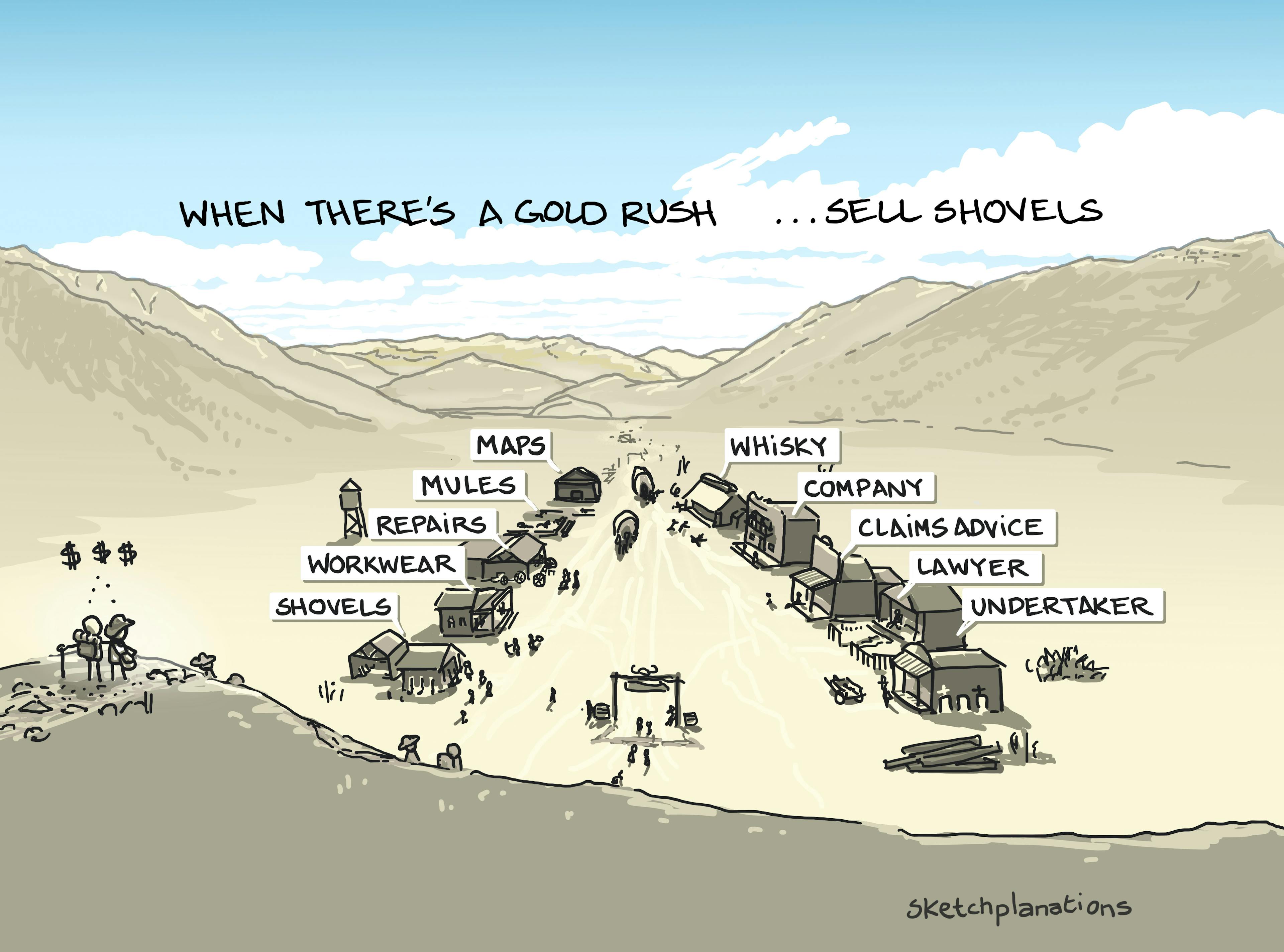

I love this age-old wisdom. It may be about the gold rush, but I see it everywhere to this day. When everyone is trying to get rich in the sensational way, the people who reliably do well are those who sell to the people trying to get rich. In the gold rush, prospectors and miners seeking their fortunes headed up to the hills to find gold. A few of them found it. But, like all get-rich-quick schemes, the vast majority of them found no gold claims that made their fortune. Whether they got lucky or not, they needed tools—shovels, picks, buckets, pans. They also might have purchased mules, food, lodging, supplies, guidance, and maybe they bought whiskey to drown their sorrows. Famously, they might have needed hardwearing work clothes, of which denim was the perfect solution. And the interesting thing about all the people who sold to the prospectors is that they could make money whether their customers found gold or not. They can sell to the people winning and the people losing. The saying has at least a few different forms: The secret to getting rich in a gold rush is selling picks. When Everybody Is Digging for Gold, It’s Good To Be in the Pick and Shovel Business Don’t dig for gold, sell shovels. Some Modern Examples Selling shovels in the gold rush is the classic example, but modern-day examples abound. It often looks like selling access, tools, platforms or advice to people chasing a quick buck. Investment brokers and platforms that charge for trading.

Brokers and platforms make a profit when the market dives and when it soars. The more activity there is, the better they do. Exchanges and marketplaces.

Where the trading happens, whether it’s stocks and shares, second-hand goods, or vintage furniture. Tooling and platforms.

YouTube, AWS, Domain providers profit the more people try to seek their fortune. “How to make money doing X” courses and education.

Looking to make money doing X? Buy the course, and you’ll get the exact steps to replicate the winning strategies. Earn on YouTube. Monetise your newsletter. Publish your book. And some slightly more oblique examples: Transformation industries.

Gyms and supplements sell the promise of transformation, regardless of whether people achieve their goals. Self-help and productivity.

Just implement this new productivity tip, and you’ll transform your prospects. In each case, millions of people purchase without achieving the ends they were hoping for. But the shovel-sellers do well either way. A Simple Formula It’s seductive because, in classic survivorship bias, we see the people who’ve made it: the YouTubers with millions of followers, the crypto early adopters who didn’t sell in a crash, the property flippers who bought at the right place and time. But sometimes the people doing best seem to be those promising to teach you how to get rich that way In most of these cases there’s: A new way of making money High-visibility successes A self-reinforcing loop: the more people follow or buy your course, program, or product promising success, the more successful you look, and the more legitimate your service seems. Try Selling Shovels I share this because I regularly reflect on it as a lens for my own activity. Am I trying to follow the herd and the gold rush? Maybe I would be better off helping others in their journey for gold? How could I support them instead of rushing myself? It’s tempting to imagine yourself as one of the winners of the gold rush. But all that activity creates opportunities to support the prospectors. Selling shovels means your future is less dependent on being lucky, early, or exceptional and hitting a gold seam. Or maybe I'm just jealous ;o) -- As usual, if you’re looking for the origins of the phrase selling shovels in a gold rush, Quote Investigator has done the work for you. Related Ideas to Selling Shovels in a Gold Rush More business and entrepreneurship advice and ideas in sketches: Sell painkillers, not vitamins To scale, do things that don’t scale Starting a company is like jumping off a cliff The Butcher, the Brewer, the Baker The twin engines of altruism and ambition Don’t ask the barber if you need a haircut The Big Ideal TM The Golden Circle—People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it Survivorship Bias Optimism Bias Contentment: what you have, relative to what you wantI love this age-old wisdom. It may be about the gold rush, but I see it everywhere to this day. When everyone is trying to get rich in the sensational way, the people who reliably do well are those who sell to the people trying to get rich. In the gold rush, prospectors and miners seeking their fortunes headed up to the hills to find gold. A few of them found it. But, like all get-rich-quick schemes, the vast majority of them found no gold claims that made their fortune. Whether they got lucky or not, they needed tools—shovels, picks, buckets, pans. They also might have purchased mules, food, lodging, supplies, guidance, and maybe they bought whiskey to drown their sorrows. Famously, they might have needed hardwearing work clothes, of which denim was the perfect solution. And the interesting thing about all the people who sold to the prospectors is that they could make money whether their customers found gold or not. They can sell to the people winning and the people losing. The saying has at least a few different forms: The secret to getting rich in a gold rush is selling picks. When Everybody Is Digging for Gold, It’s Good To Be in the Pick and Shovel Business Don’t dig for gold, sell shovels. Some Modern Examples Selling shovels in the gold rush is the classic example, but modern-day examples abound. It often looks like selling access, tools, platforms or advice to people chasing a quick buck. Investment brokers and platforms that charge for trading.

Brokers and platforms make a profit when the market dives and when it soars. The more activity there is, the better they do. Exchanges and marketplaces.

Where the trading happens, whether it’s stocks and shares, second-hand goods, or vintage furniture. Tooling and platforms.

YouTube, AWS, Domain providers profit the more people try to seek their fortune. “How to make money doing X” courses and education.

Looking to make money doing X? Buy the course, and you’ll get the exact steps to replicate the winning strategies. Earn on YouTube. Monetise your newsletter. Publish your book. And some slightly more oblique examples: Transformation industries.

Gyms and supplements sell the promise of transformation, regardless of whether people achieve their goals. Self-help and productivity.

Just implement this new productivity tip, and you’ll transform your prospects. In each case, millions of people purchase without achieving the ends they were hoping for. But the shovel-sellers do well either way. A Simple Formula It’s seductive because, in classic survivorship bias, we see the people who’ve made it: the YouTubers with millions of followers, the crypto early adopters who didn’t sell in a crash, the property flippers who bought at the right place and time. But sometimes the people doing best seem to be those promising to teach you how to get rich that way In most of these cases there’s: A new way of making money High-visibility successes A self-reinforcing loop: the more people follow or buy your course, program, or product promising success, the more successful you look, and the more legitimate your service seems. Try Selling Shovels I share this because I regularly reflect on it as a lens for my own activity. Am I trying to follow the herd and the gold rush? Maybe I would be better off helping others in their journey for gold? How could I support them instead of rushing myself? It’s tempting to imagine yourself as one of the winners of the gold rush. But all that activity creates opportunities to support the prospectors. Selling shovels means your future is less dependent on being lucky, early, or exceptional and hitting a gold seam. Or maybe I'm just jealous ;o) -- As usual, if you’re looking for the origins of the phrase selling shovels in a gold rush, Quote Investigator has done the work for you. Related Ideas to Selling Shovels in a Gold Rush More business and entrepreneurship advice and ideas in sketches: Sell painkillers, not vitamins To scale, do things that don’t scale Starting a company is like jumping off a cliff The Butcher, the Brewer, the Baker The twin engines of altruism and ambition Don’t ask the barber if you need a haircut The Big Ideal TM The Golden Circle—People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it Survivorship Bias Optimism Bias Contentment: what you have, relative to what you wantWWW

Read more…