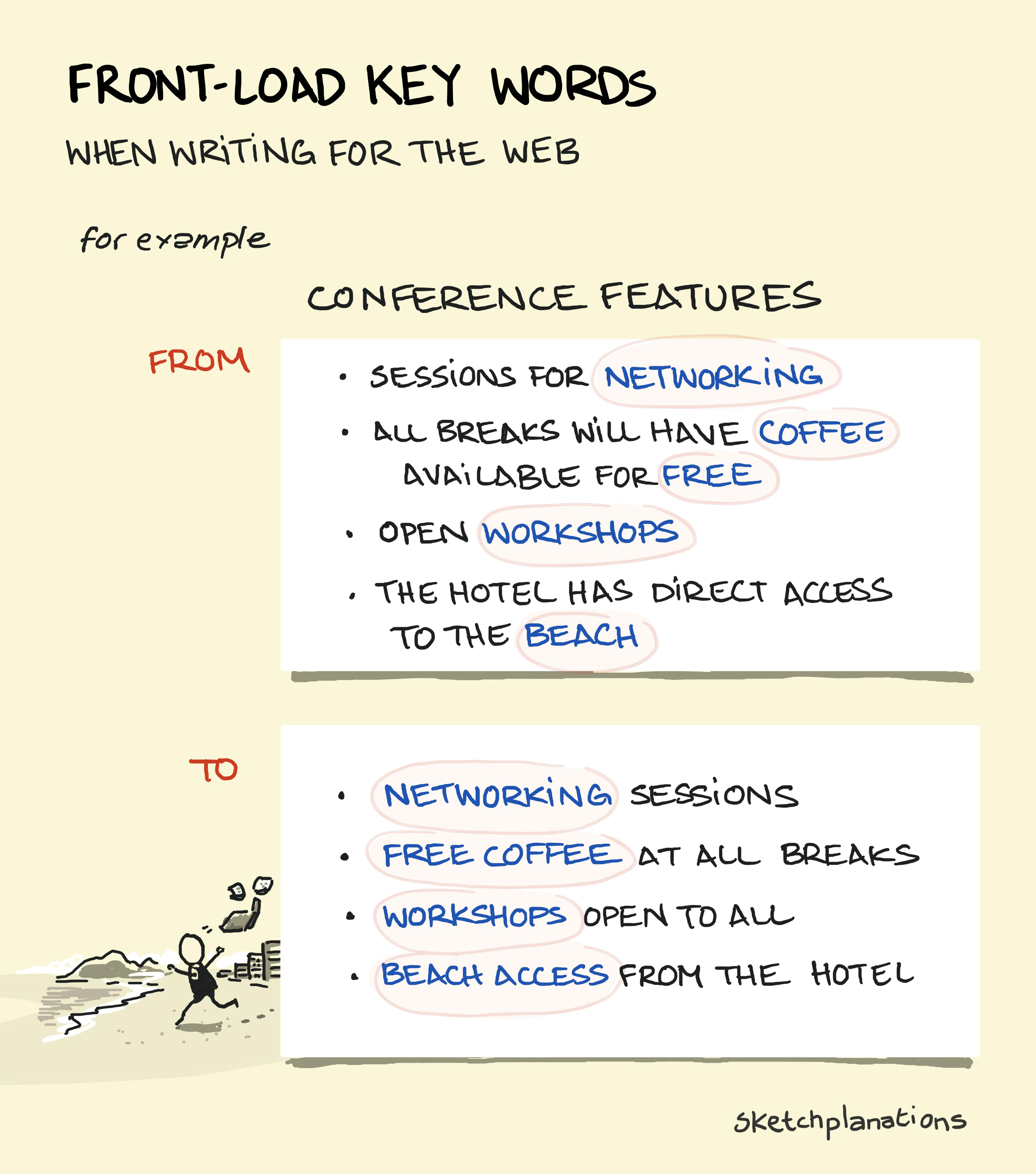

Front-load Key Words

People don’t usually want to read online—they want to get something done. This means that when deciding whether a service is worth subscribing to, figuring out which plan is better, trying to understand a set of features, or determining whether you need this product or that, people mostly just want to skim through. So the easier you can make this for them as a writer and designer, the better. One simple tweak I use regularly when writing or editing is to front-load the meaningful words in lists. What Is Front-Loading Meaningful Words? Front-loading means placing the words that signal most—those that convey meaning or make the point—right at the start, not buried in the middle or end. I learned this lesson through many painful examples of people not reading what we’d written on a page and then complaining that we never told them. Here’s a list I worked on from the welcome email to the newsletter. This was my first draft: Explore the sketch archive on sketchplanations.com Dig in more with the Sketchplanations podcast. At 50+ episodes and counting. Fun, lighthearted and thought-provoking, my co-hosts and I take a sketch each week and dive in, sometimes with an expert guest to help us out. Prefer reading off devices? Me too. You can catch up on past sketches with my book Big Ideas Little Pictures Revision: More to explore 🔍 The full archive on sketchplanations.com 🎙️ Sketchplanations podcast—50+ lighthearted episodes diving into one sketch a week, often with expert guests 📔 Big Ideas Little Pictures—Prefer reading off devices? Me too. A collection of nearly 150 of my favourite sketches in a book (emojis optional, but in this case, they perhaps are an even better scanning tool. Or not.) Now, you may prefer the first one, but if you’re in a hurry or still undecided about whether this is worth reading, the second is more likely to convey the key points I wanted to share. No doubt more improvements are still possible. Because links have formatting that draws attention, it also helps to have each of those at the start, or at least in a consistent place, to aid scanning and skimming—as in the revision where your eyes can scan straight down the key information. This supports the F-Shaped Reading pattern, in which people often scan pages in an F shape. The revision is also shorter, so it’s more likely to be read. This is not a tip for writing novels. Nor, perhaps, for your email newsletter. But in situations where people are skimming—often not even sure they want to read your writing—it helps a lot. That includes almost everything on the web except long-form essays, but also plenty that’s off the web too: Safety notices Public transport information Shop signage Job descriptions Menus Instruction manuals Onboarding checklists Property listings Event schedules And more. Front-Loading to Refine your Link Text The same front-loading principle applies to the words you use within link text, for example, take this sentence and link: For another use case, see the F-Shaped Reading pattern For scanning, this is generally better as: For another use case, see the F-Shaped Reading pattern. ...because scanning the text of the link itself immediately tells me “F-Shaped Reading” rather than “see the...” Link text is one of those places I always want to improve. I made a ‘click here‘ category of sketches to get across this idea: Rewrite to avoid click here. For another post. When time is short, attention is limited, or people just want the next step. So, start with the most useful words. Related Ideas to Front-Load Meaningful Words in Bullets Also see: Front-load names to cue attention F-Shaped Reading Cognitive Overhead Micro-editing Redundant Words By Monkeys — Write actively The First Draft is Always Perfect Happy talk must diePeople don’t usually want to read online—they want to get something done. This means that when deciding whether a service is worth subscribing to, figuring out which plan is better, trying to understand a set of features, or determining whether you need this product or that, people mostly just want to skim through. So the easier you can make this for them as a writer and designer, the better. One simple tweak I use regularly when writing or editing is to front-load the meaningful words in lists. What Is Front-Loading Meaningful Words? Front-loading means placing the words that signal most—those that convey meaning or make the point—right at the start, not buried in the middle or end. I learned this lesson through many painful examples of people not reading what we’d written on a page and then complaining that we never told them. Here’s a list I worked on from the welcome email to the newsletter. This was my first draft: Explore the sketch archive on sketchplanations.com Dig in more with the Sketchplanations podcast. At 50+ episodes and counting. Fun, lighthearted and thought-provoking, my co-hosts and I take a sketch each week and dive in, sometimes with an expert guest to help us out. Prefer reading off devices? Me too. You can catch up on past sketches with my book Big Ideas Little Pictures Revision: More to explore 🔍 The full archive on sketchplanations.com 🎙️ Sketchplanations podcast—50+ lighthearted episodes diving into one sketch a week, often with expert guests 📔 Big Ideas Little Pictures—Prefer reading off devices? Me too. A collection of nearly 150 of my favourite sketches in a book (emojis optional, but in this case, they perhaps are an even better scanning tool. Or not.) Now, you may prefer the first one, but if you’re in a hurry or still undecided about whether this is worth reading, the second is more likely to convey the key points I wanted to share. No doubt more improvements are still possible. Because links have formatting that draws attention, it also helps to have each of those at the start, or at least in a consistent place, to aid scanning and skimming—as in the revision where your eyes can scan straight down the key information. This supports the F-Shaped Reading pattern, in which people often scan pages in an F shape. The revision is also shorter, so it’s more likely to be read. This is not a tip for writing novels. Nor, perhaps, for your email newsletter. But in situations where people are skimming—often not even sure they want to read your writing—it helps a lot. That includes almost everything on the web except long-form essays, but also plenty that’s off the web too: Safety notices Public transport information Shop signage Job descriptions Menus Instruction manuals Onboarding checklists Property listings Event schedules And more. Front-Loading to Refine your Link Text The same front-loading principle applies to the words you use within link text, for example, take this sentence and link: For another use case, see the F-Shaped Reading pattern For scanning, this is generally better as: For another use case, see the F-Shaped Reading pattern. ...because scanning the text of the link itself immediately tells me “F-Shaped Reading” rather than “see the...” Link text is one of those places I always want to improve. I made a ‘click here‘ category of sketches to get across this idea: Rewrite to avoid click here. For another post. When time is short, attention is limited, or people just want the next step. So, start with the most useful words. Related Ideas to Front-Load Meaningful Words in Bullets Also see: Front-load names to cue attention F-Shaped Reading Cognitive Overhead Micro-editing Redundant Words By Monkeys — Write actively The First Draft is Always Perfect Happy talk must dieWWW

Read more…