Murphy's Law

👇 Get new sketches each week

When you're in a hurry and the light turns red. When your toast falls butter side down. When you visit the shop on the only day it's closed—all classic Murphy's Law.

What is Murphy's Law

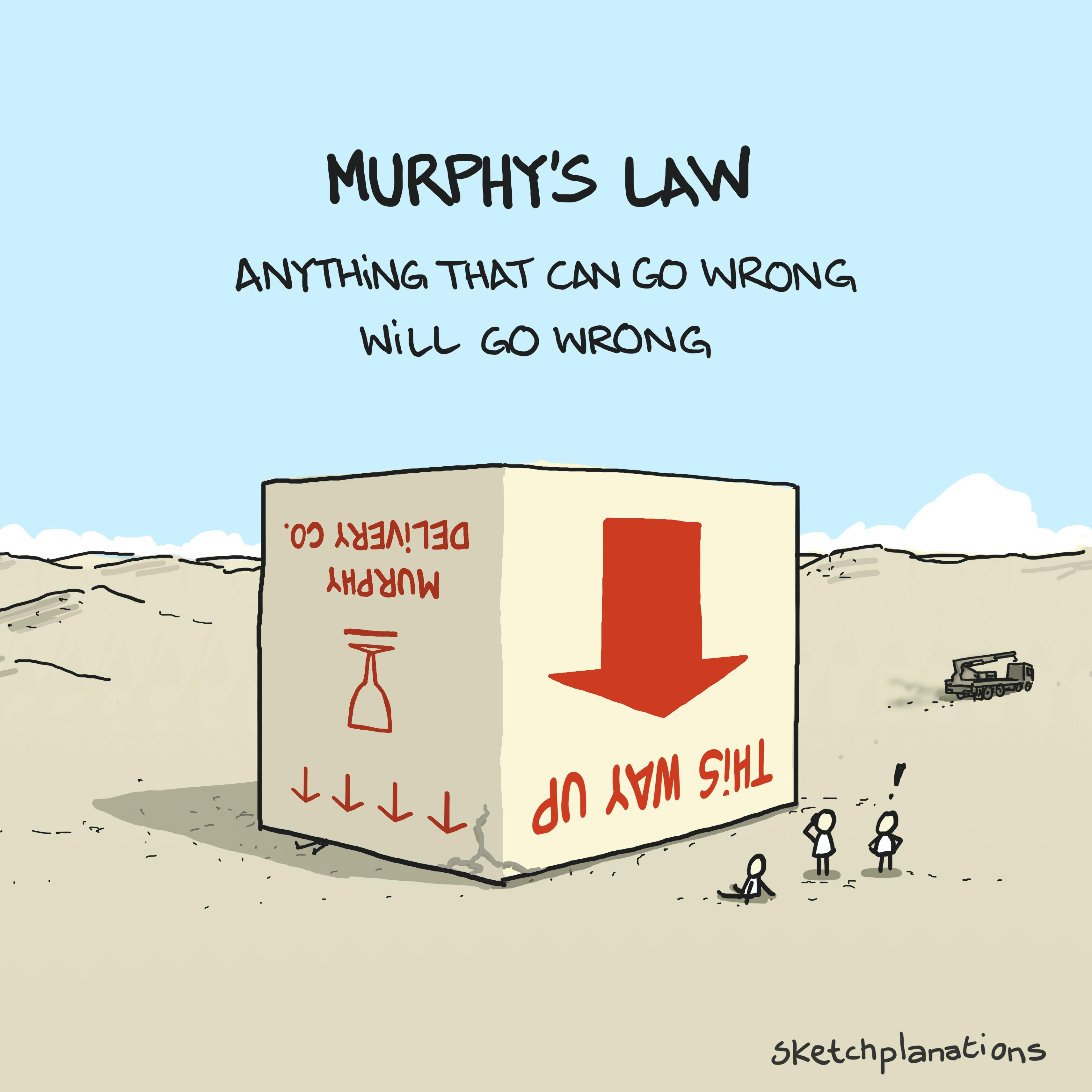

Murphy's Law is: Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.

Other common phrasings of Murphy's Law include:

- If it can go wrong, it will

- If something can go wrong, it will go wrong

- Whatever can go wrong, will go wrong.

I'd always taken the meaning of Murphy's Law as a pessimistic view of the universe. A kind of "well, typical," "just my luck," "of course it would happen to me," kind of attitude. People invoke it as a convenient excuse for things not going well — a chance to complain and feel that events weren't their fault.

My dad always called it Sod’s Law, the more British version of the phrase.

I've come to realise that the original meaning of Murphy's Law was more optimistic than pessimistic.

For instance, if a box should be a particular way up, we should assume that at some point, someone will put it the wrong way up. So maybe we could design it so that it can't be placed the wrong way up, forcing people to orient it correctly.

If you think of the ways something could go wrong and plan for them, there's less chance of them getting you.

The Murphy's Law Legend

There's a strong—though disputed—origin story for Murphy's Law. The most common story goes something like this.

A U.S. Air Force team at Edwards Air Force Base was investigating the effects of extreme acceleration and deceleration on the human body using rocket sleds. They installed new strain gauges, supplied by an engineer named Edward Murphy. But they found the gauges didn't work.

Murphy was called in and discovered that someone had installed the gauges incorrectly. Frustrated, he reportedly said something along the lines of: "If that guy has any way of doing something wrong, he'll do it wrong."

The team were in the habit of inventing "laws" for different members of the team. George Nichol's recalls changing the initial phrasing to If it can happen, it will happen. And in a press conference, John Paul Stapp, the inspirational team lead who subjected himself to the extreme testing, shared Murphy's Law as: Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.

It caught on.

Murphy himself later said about the strain gauges, "I made a terrible mistake—I didn't cover every possibility for putting these together." In other words, the lesson was not that fate conspires against you, but that if something can be done incorrectly, it eventually will be—so design to prevent it.

This connects Murphy's Law to concepts like foolproof design, forcing functions, or the Japanese poka-yoke (mistake-proofing).

Incidentally, the team also coined Stapp's Law as: The universal aptitude for ineptitude makes any human accomplishment an incredible miracle.

Stapp's work in understanding the limits of the body didn't just improve aerospace safety. He saw that more people, even in the Air Force, were dying in car crashes than aircraft accidents. Rather than just focusing on preventing crashes, with a very Murphy's Law mindset, Stapp instead asked, When the inevitable car crash does happen, how can we prevent people from dying? His advocacy helped bring about seatbelts, safety glass, and eventually airbags—saving countless lives.

But we love a good story. Fred Shapiro, a law librarian and editor of the Yale Book of Quotations, disputes this as the origins of Murphy's Law. He also offers us these wise words: "Anytime someone tells you 'Mark Twain said this,' the one thing you know is that Mark Twain didn't say that."

Misunderstanding Murphy's Law

A few cognitive biases make us notice failures more than successes:

The frequency illusion naturally makes us more aware of what's top of mind—if we're looking for bad things happening to us, we'll start to notice them more frequently.

Survivorship bias leads us to overlook all the times that something bad didn't happen to us.

And because unfortunate events easily stick in our memory, salience bias can lead us to overestimate how common they really are.

For instance, my Law of Lockers is that if you're the only two people in the changing rooms, your lockers will be next to each other. But of course I'm sure I'm ignoring all the many more times our lockers weren't on top of each other.

Murphy's Law as an Optimistic Viewpoint

And so, in a classic Murphy's Law style example, I've concluded that I generally misunderstood Murphy's Law.

It doesn't have to highlight all the bad luck I have. Instead, it can be a call to consider what can go wrong, and given there's a chance that it will, prepare for that so it doesn't.

Related Ideas to Murphy's Law

- Muphry's Law: when criticising spelling or grammar, you'll make a mistake yourself.

- Plan ahead

- A mistake is not something to be determined after the fact

- Hanlon's Razor

- Thoughtless acts

- Forcing function

- Kitchen table survival skills

- Unknown unknowns

- Eponyms

- Finagle's Law: Anything that can go wrong, will—at the worst possible moment.

More about Murphy's Law and its origins:

- Nick Spark's book A History of Murphy's Law

- A super Decoder Ring podcast episode on Murphy's Law by Willa Paskin, from where I learned much of the origins

- I did several different versions of this sketch and kept coming back to the wonderful Far Side cartoon of the penguin and the banana skin .

- O'Toole's comment on Murphy's Law: Murphy was an optimist.

- Just because someone called it a law doesn't mean it is.