Canal Locks

👇 Get new sketches each week

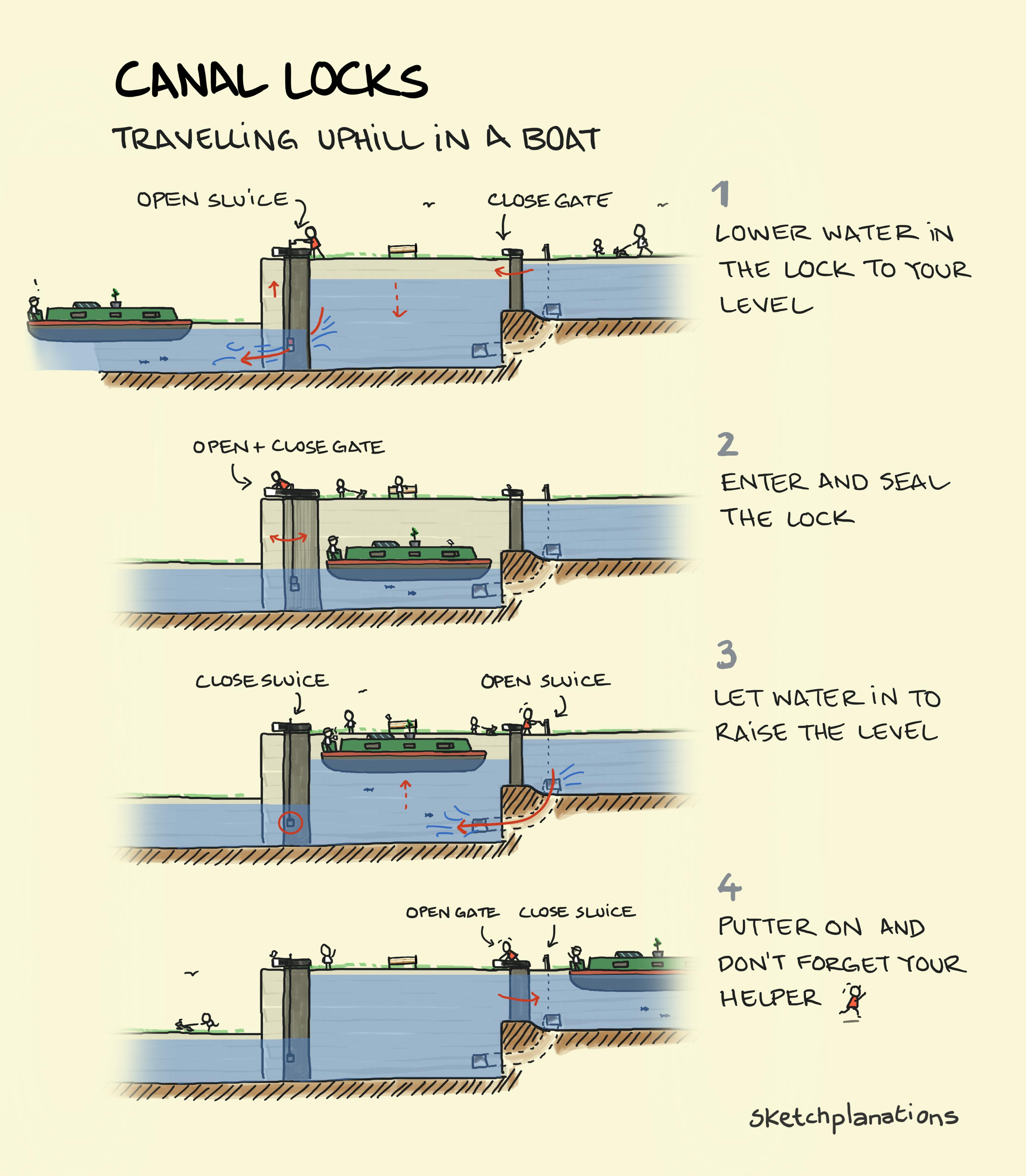

There's something remarkable about a boat travelling uphill. Canal locks are a simple yet ingenious system that has made it possible for centuries.

How a Canal Lock Works

The humble lock gate has more to it than first appears. Here's how one of the most common types works.

For a boat approaching a lock from below and meeting a closed gate:

1. Bring the water to your level

Close the top gate to seal the lock. Then, open the sluice (or paddle) in the lower gate — often a sliding panel — by cranking it with the ever-handy windlass (a simple metal crank that fits onto square spindles on the lock mechanism).

2. Enter and seal the gate

Once the water is at the lower level, you can push the giant counterweights to open the gate and steer the boat inside. Don't nudge too far forward, or you'll bump the cill, a stone ledge at the top end of the lock. Close the gate behind you and shut the sluice to stop water escaping.

3. Raise the water level

With the lock sealed, open the top sluices. These often feed through side channels or culverts, letting water in gently from upstream, usually below the surface, to reduce turbulence. You'll gradually float upward as the lock fills.

4. Head upstream

Once the water level matches the upper pound (the upper stretch of water), open the top gates, close the sluices, and cruise on your way.

The same principles, in reverse, work for approaching the lock from above.

As you can imagine, operating locks is much harder work if you're boating solo.

Water Supply for Canals

One thing that makes all this possible is a steady supply of water. You can't rise in a lock without water to fill it. So, canal builders had to ensure the canal had enough water to stay navigable and to keep the locks functioning.

For some of the London canals, the builders created huge reservoirs with long feeder channels to ensure the canals had enough water. In some places, water is pumped back uphill to be reused at the top of a flight.

Canal water doesn't flow much — it's a closed system in many places. I'd heard that, in principle, it only takes one lock's worth of water for a boat to travel down a whole flight of locks: each lockful of water carries the boat one step down and ends up in the next pound. So, a boat going down several locks essentially transfers a single chamber's worth of water from the top to the bottom.

But in practice, how much water gets used depends on boat traffic from either side, whether you meet locks full or empty, and water-saving features such as side pools. In my research, it wasn't as simple as it seemed.

The Mitre Gate

Holding back tonnes of water is no small task. Mitre gates are angled to meet, pointing upstream and forming a shallow V. This shape means the water pressure pushes the gates closed, creating a tight seal — the water effectively locks itself in.

A stone arch bridge uses a similar principle—compression strengthens the structure under pressure.

Leonardo da Vinci sketched an early design for the mitre gate around 1500. The design still looks like a modern lock gate. Not bad for an invention 500+ years ago.

Understandable Engineering at Large

Canal locks are like playing with water in the bath but on a massive scale. They're inherently satisfying to watch and operate. At their peak, they revolutionised transport across much of Europe and beyond.

The same basic idea still operates in the Panama Canal, where giant ships are lifted 26 metres over the isthmus simply by filling and draining the lock chambers in sequence.

The dimensions of a lock determine the size of the boat that can pass through. Panamax is the maximum size a ship can be to fit through the Panama Canal—a constraint that shapes shipbuilding worldwide.

In the UK, Tardebigge Locks has 30 locks to raise boats 67m over just 3.6km. Not to be outdone, Caen Hill Locks on the Kennet and Avon Canal has 29 Locks, 16 of which are in a straight line, rising 72m over 2.1km.

For a single, remarkable lock, have a look at Falkirk Wheel lock in Scotland. It's the "one and only rotating boat lift", which replaces 11 locks with a 2 min rotating journey lifting boats through the air.

Full disclosure:

We recently took a canal boat trip on London's Regents Canal, including a visit to London's Canal Museum .

Far from its industrial heyday, the whole place was buzzing with people out for leisure up and down the length of the journey. The towpath—horses towed the barges by walking alongside—was packed with walkers, joggers and cyclists.

And it never failed to fascinate when the boats moved up or down a lock.

Engineering at work!

Related Ideas to Canal Locks

Also see:

- Everyone's a Geek About Something

- Buoyancy: how do mega ships float?

- The Plimsoll Line

- Siphon

- Kayak vs Canoe

- Strahler Stream Order

- Iceberg orientation

- Why ice doesn't sink

- Naismith's Rule (including the term "lock miles")

- Rivers and Buckets