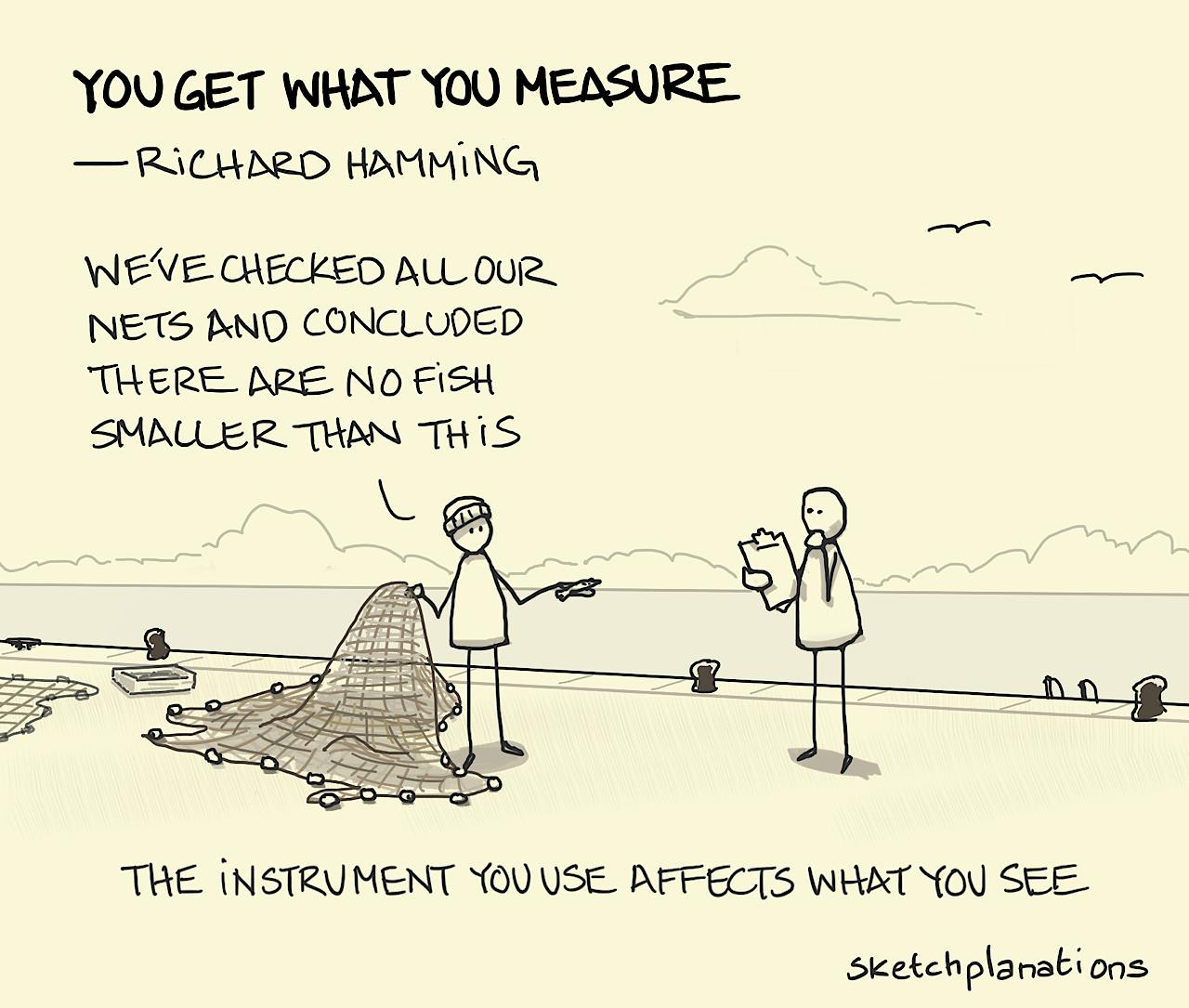

You get what you measure

👇 Get new sketches each week

Sir Arthur Eddington, an English astrophysicist, told a short story involving a scientist studying fish by pulling them up with nets. After checking all the fish hauled up, the scientist concludes that there is a minimum size of fish in the sea. But the fish seen were determined by the size of the holes in the net, the smaller ones having slipped through, unmeasurable. The instrument you use affects what you see. Or as Richard Hamming puts it: "You get what you measure."

This analogy provides a nice concrete example of a phenomena that affects us routinely in more subtle ways. What and how we choose to measure affects the conclusions we draw. So, a website may easily measure sales and bounce rate for its pages, while things like trust, authority or satisfaction, which may be more significant longer-term metrics, go unmeasured.

Richard Hamming points out:

"There is always a tendency to grab the hard, firm measurement, though it may be quite irrelevant as compared to the soft one which in the long run may be much more relevant to your goals. Accuracy of measurement tends to get confused with relevance of measurement, much more than most people believe. That a measurement is accurate, reproducible, and easy to make does not mean it should be done, instead a much poorer one which is more closely related to your goals may be much more preferable. For example, in school it is easy to measure training and hard to measure education, and hence you tend to see on final exams an emphasis on the training part and a great neglect of the education part."

Also see:

- Goodhart's Law

- What gets measured gets better (an earlier take on this)

- Campbell's Law

- Understanding reliability and validity

Quote from Chapter 29, You get what you measure, of Richard Hamming's, The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn .

If you happen to be in the business of doing research or science Richard Hamming's Bell Lab's talk, You and Your Research (pdf), is an excellent read.